Opening

“Summer in Tokyo. The streets shimmer with heat, the air feels heavy, and the sunlight bounces off the pavement like an oven. Then you see it—a mound of crystal-clear ice, glistening under a cascade of colorful syrup.

One bite and it melts instantly on your tongue, sending a wave of cool sweetness down your throat, refreshing not just your body but your soul. This is kakigōri, Japan’s iconic summer treat.

Today you can find it in convenience stores, cafés, and gourmet dessert shops across the country, but its story goes back over a thousand years. This is the journey of kakigōri—from a delicacy for ancient aristocrats to the creative, Instagram-worthy dessert you can enjoy in modern Tokyo.”

Heian Period: Ice for the Aristocracy Only

“The earliest written record of kakigōri appears in The Pillow Book, a classic work of Japanese literature written in the 10th century. At that time, the capital was Kyoto, and summers were hot and humid.

Ice was harvested in winter from mountain ponds and stored in insulated huts called himuro, using straw and leaves to keep it from melting. In summer, it was transported down to the city by horse or on foot—a journey so difficult that much of the ice would melt along the way.

This meant that only the Emperor, court nobles, and a handful of high-ranking monks could taste it. They would shave the ice thinly and pour over it a sweet syrup made from the sap of a vine plant called amazura. Imagine the luxury—while most people could barely dream of seeing ice, the elite were enjoying it in elegant gardens, composing poetry, and savoring its fleeting coolness.

In those days, ice was more than food—it was a symbol of status and power.”

Edo to Meiji: Ice Arrives in the City

“By the late Edo period, around the 18th and 19th centuries, a new trade began to flourish: transporting natural ice from rural areas to the cities. In winter, thick ice was cut from lakes and ponds, packed in straw, and stored until summer. Then it was shipped by river or sea to Edo—now Tokyo.

Still, ice was expensive, reserved for wealthy merchants and special tea houses. But Edo’s vibrant merchant culture adored anything novel, and the idea of tasting real ice became a dream for many city dwellers.

In the Meiji era, Western technology transformed the scene. Ice-making machines were imported from abroad, and artificial ice could be produced in large quantities. Ice went from a rare treasure to something far more accessible. Street stalls and small shops began serving kōri-mizu—shaved ice topped with sweet syrup. The first colorful flavors, like bright red strawberry and zesty lemon, fascinated the people of the time, both for their refreshing taste and their vivid appearance.”

Shōwa Summer: Festivals, Beaches, and the Flag of Ice

“After World War II, Japan’s rapid economic growth brought ice production facilities to every region. By the mid-20th century, kakigōri had become a symbol of summer itself.

At local summer festivals, you would see blue flags with a large white kanji character for ‘ice’ flapping in the wind. Beneath them, the hand-cranked ice machines made a cheerful scraping sound, turning solid blocks into fluffy piles served in paper cups or glass bowls.

Syrups came in bright colors—deep blue ‘Blue Hawaii,’ vivid green melon, and classic red strawberry. Children lined up with coins in hand, their eyes sparkling at the sight of the rainbow-colored syrups. Even the sharp ‘brain freeze’ from eating too fast was part of the fun.

Beaches and swimming pools also became kakigōri’s stage. Sunburned skin cooled instantly under each spoonful, creating a memory that blended the extremes of summer heat and icy refreshment. In this era, kakigōri was simple, affordable, and always shared—an edible piece of summer nostalgia.”

Reiwa Tokyo: The Evolution of Kakigōri Culture

“Fast forward to modern-day Tokyo, and kakigōri has transformed beyond recognition. Once a seasonal festival snack, it is now a year-round gourmet dessert.

Specialty shops serve ice shaved so thin it feels like snowflakes dissolving on your tongue. Many use tennen-gōri—natural ice slowly frozen over weeks in winter, which melts more slowly and has a soft, pure taste. Others infuse the ice itself with flavors like tea, fruit, or herbs, ensuring the last spoonful is as rich as the first.

Toppings go far beyond syrup. Imagine a towering mound of ice layered with matcha cream and azuki beans, or mango purée with fresh berries, or even basil and spice combinations that challenge the idea of what dessert can be.

Presentation has become an art form—ice shaped like flower petals, decorated with edible gold leaf, fresh flowers, or intricate sauces. Many creations are designed with social media in mind: tall, colorful, and photogenic from every angle.

There’s also a storytelling trend—flavors inspired by summer fireworks, seasonal landscapes, or even a chef’s travel memories. In this way, kakigōri has evolved into an experience, not just a dish.

This change is driven by Tokyo’s unique mix of tradition and innovation, the influence of Instagram and TikTok, and the passion of chefs who treat kakigōri like haute cuisine.”

The Charm of Enjoying Kakigōri in Tokyo

“What makes Tokyo so exciting for kakigōri lovers is variety. In historic districts, you can find traditional Japanese-style flavors like matcha and roasted green tea served in serene tea rooms. In youthful neighborhoods, you might discover experimental versions with global influences, from tiramisu-style creations to tropical fruit blends.

Seasonal changes are another draw. In spring, you might taste cherry blossom kakigōri. In summer, melons and mangoes dominate. In autumn, chestnut and sweet potato appear, while winter brings strawberries and rich chocolate combinations.

For travelers, this means you can taste all four seasons of Japan in a single city. And because Tokyo is a metropolis, kakigōri can be enjoyed in many settings: in cool cafés on a sweltering day, in department store lounges while shopping, or even in underground mall cafés on a rainy afternoon. The accessibility, combined with endless creativity, makes Tokyo a paradise for shaved ice enthusiasts.”

Ending

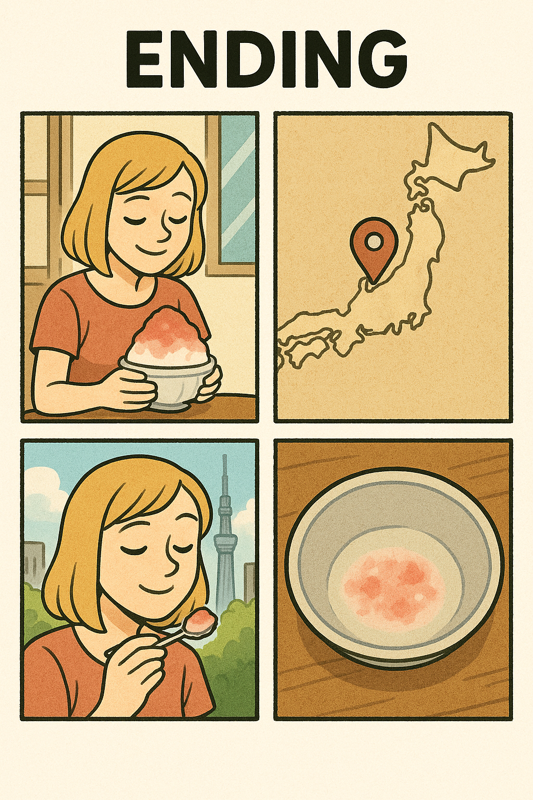

“Over a thousand years ago, ice was a rare treasure enjoyed only by Japan’s elite. Over time, it became the joy of summer festivals, and today it stands as a year-round art dessert in the heart of Tokyo.

A bowl of kakigōri is more than just ice and syrup—it is a frozen story that captures Japan’s history, its seasons, its culture, and the creativity of its chefs.

So, when you visit Tokyo, what kind of kakigōri would you like to try first? Let us know in the comments. And if this journey through Japan’s coolest tradition made you smile, give this video a thumbs up and subscribe for more.

In our next episode, we’ll explore the shaved ice cultures of the world—and how you can taste them all without leaving Tokyo.”